Hi dear readers!

Damn time flies. May 31 was two years since the launch of Birdseed, scattering seeds with a flourish to see what would spring up. It’s been nearly 80 issues to your inboxes exploring themes like the liberation of sobriety, the persistence of “bad men,” the wisdom of houseplants, the wildness of creativity, and the dissolution of scaffolding as we age — all through a Buddhist lens smudged with humor and word play.

I’m continually delighted to see what resonates most (or least) for you (or should I saw what you resonate with). Often it’s the pieces that have nagged me — that I feel I must publish right then (typos and all) — that’ve had the deepest, softest landings with you. This supports my hunch that, while I spend a great deal of time stewing and crafting what I write, the most important thing is to get out of its way. This is my main approach to creativity lately: stay grounded and get out of the way.

Thank you so much for being here, it means a great deal. And if you find yourself enjoying what you read — if it supports your heart, invites you to pause and reflect, or enriches your life in some way — please consider supporting my work for $6 a month or $60 a year. This enables me to keep going, and I’m very grateful for that.

I am a dot connector, a constellator, a seed sewer, a chill provocateur.

I am completely in the process of molting, still.

I am rooting for you. I am rooting for us.

Now, on to the writing…

Dear readers: I know some of you personally for many years, but many more I don’t know at all. And yet you know many aspects of me: bits and bobs as well as longer narrative arcs of my life, painful and joyful, both current and past. Things some might reserve just for IRL heart friends.

If you don’t know me in “real life,” in what way do you feel that you know me? Who am I to you? And who are you to me? What is this relationship?

In a recent issue of her truly great newsletter, journalist Ann Friedman explores parasocial relationships. Parasocial is when you know more about someone than they know about you, if they even “know” you or that you exist at all! You can also have a parasocial relationship with an entity (a houseplant?) or group (the Buffalo Bills?).

How many parasocial relationships would you say you’re in? Are you poly-parasocial-amorous? Are you aware of anyone drinking up information about you and pining after you? How do you comport yourself when you find yourself on one end of the looking glass, and then the other?

Many (most? can someone fact check this for me) things in life are asymmetrical, which I suppose could be another way of saying unfair or unjust. Lopsided. That is not unilaterally, inherently bad. But imbalance always has implications.

While celebrity culture has long lent itself to parasocial relationships (e.g. me knowing every detail about and fawning over Claire Danes in 1998), the proliferation of personal shares made possible by social media has fostered a culture of perception that we “know people” when we only know their performance. It’s also stoked greater expectation for personal details — because we can know, we should.

I ran into an acquaintance on the street with my newborn son. He was surprised, and apologized sheepishly for missing the post where I announced I’d had a kid. I hadn’t posted one at that point!

Friedman writes,

“The term ‘parasocial’ is now common parlance. We have entered an advanced stage of our collective shift from a media economy of publications to one of individuals. The currency is no longer just the work itself, it’s the work plus the perceived relationship. That feeling of connection.”

“In the parasocial economy, personal details are currency. […] There is always a cost to revealing yourself, so you better be sure about what you’re getting in the exchange. Is it book sales? Is it audience loyalty? Is this actually part of your creative practice? Trying to figure out how to share yourself on your terms is, indeed, exhausting. It’s also a privilege and a hallmark of success.”

Connection is where I dwell and what I purposefully seek to cultivate here, so it is in that spirit that I share. Friedman, who hardly ever shares about her personal life, points out that any morsels of personal info across the asymmetry can awaken a voracious appetite for more — that the parasocial dynamic can set in motion an ever more abstracted, de-personalized dynamic where entitlement and projection replace actual connection.

While privacy settings and Instagram’s “close friends” lists might give us the perception that we’re in charge of who gets what information about us, that’s mostly not the case. I know this firsthand. I’ve always been a highly secretive Scorpio rising in part because I was an unabashed starer as a child and continue to be a highly skilled eavesdropper.

Parasocialism is everywhere you look.

But it’s how we operate in the face of that asymmetry and how we allow knowledge (or lack of it) to fuel delusion that matters more.

On the cusp of my 13th birthday, overwhelmed with Olympics fever, I medaled in the Parasocial Olympic Games. An excerpt from my journal:

“I am obsessed with the [1996] girls US Gymnastics Team. I want to know what they are doing at this very moment, what they’re like, what they wear, and most of all be their friend. I wish I took gymnastics so I could be on the same team [LOL], crying & rejoicing together. Or maybe I could just hide in the room not having to be a gymnast but still with them. [WOW, what.] I am drinking up any bit of information about them I hear. They seem perfect, I might (!!) even want to be them. Dominique Moceanu, Amanda Borden, Dominique Dawes, Kerri Strug, Amy Chow, Shannon Miller & Jaycee Phelps.”

Parasocial relationships in 1996 just hit different. Back then there wasn’t much to find on the internet about the people you were obsessed with. Ask Jeeves didn’t know shit. AltaVista was out to lunch. You were glued to the TV, poring over magazines, or just speculating among friends. Without as many or as mundane data points as we have now the dots to connect were much further apart so the fantasies were rich.

As a kid, I spent a great deal of time fantasizing in general, but when it came to celebrity infatuation, it was a major source of energy. The parasocial dynamic can convince you that you truly know the other person and this is how it was for me. I knew without a doubt that Kate Maberly, the star of the 1993 rendition of The Secret Garden, would actually truly be my best friend if only we could meet.

As silly as it all is, these deeply asymmetrical relationships served to help me get to know myself. What mattered to me, what pained me, my dreams and miseries. What are those wire things that you put around a bean to help it grow generally upward, tall and strong? Yeah, those things. That’s what my early parasocial relationships did for me. Yes at times distracted me, but ultimately helped me cultivate a more honest relationship with self.

Gnothi seauton, or “know thyself,” is a philosophical principle dating back to ancient Greece. I wrote it on the inside of my turquoise low-top converse with black pen in middle school.

It is, after all, our oldest, most important relationship of all. “Knowing” oneself is a fucking trip! Not for the faint of heart. A haunted hay ride rife with goblins which also takes you into vast fields of thousands of blooming flowers with rainbows shimmering down.

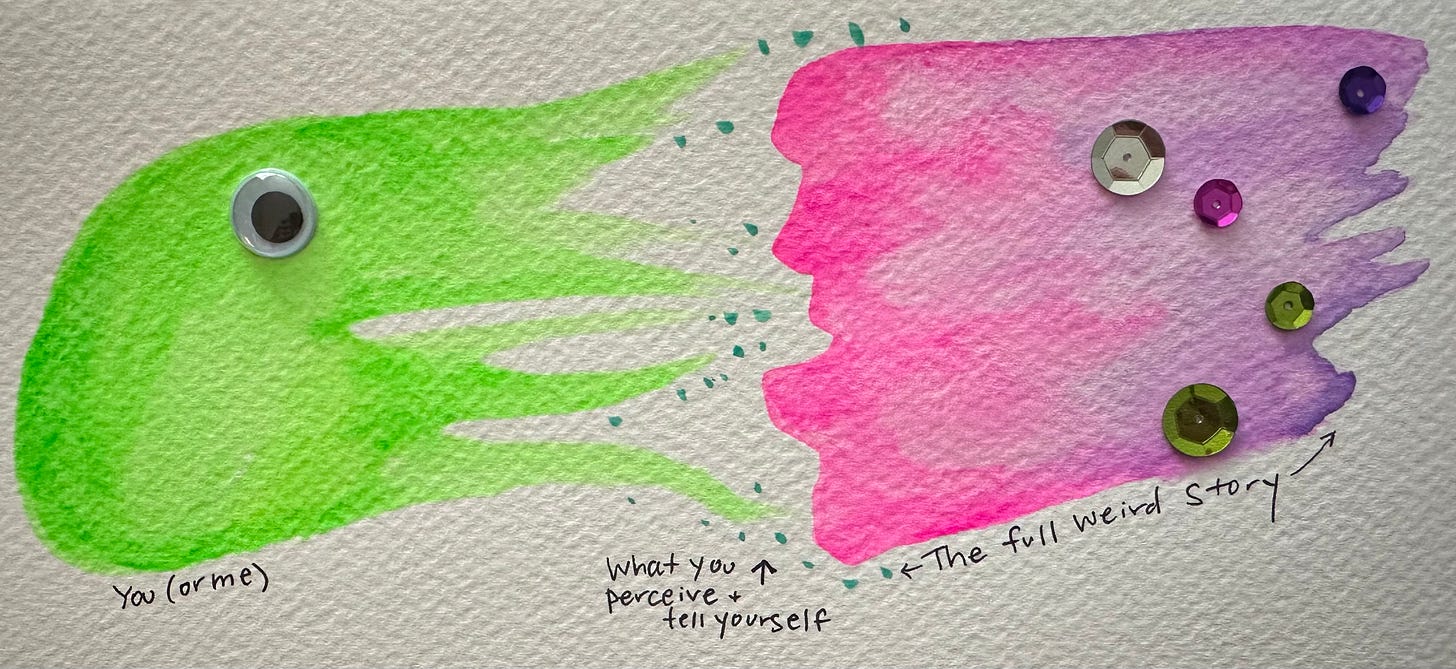

When we’re born, we don’t even have a sense of self at all. We just be! As we grow up in this weird world, we acquire narratives, cool clothes, ego blooms, emotional wounds, and the like, and the relationship with self becomes parasocial: you know a lot about some parts of you and not at all about others. As we age and soften (and this is just my guess / hope) the relationship with self becomes more expansive, it is both deeper and wiser yet with much less certainty. All the stories drop off, one by one.

I came of age in the shadow of the wildly successful public service campaign, “The More You Know.” It featured celebrities earnestly offering sobering messages designed to keep us in school, off of drugs, and out of trouble.

The campaign was so successful that it won a Peabody Award in 1993 (media’s version of a Pulitzer). But the real award was how deeply it sank into our cultural marrow, spawning SNL sketches and seeping into the colloquial. In my day, it wasn’t uncommon to utter a tongue in cheek, “the more you know” to a buddy after learning or sharing a piece of information — usually obvious.

The campaign rode on the back of the adage that knowledge is power — that the more you know something the more you can control it, win it, manipulate it, or manage it.

What a rather violent and misinformed calculation.

Knowledge is just knowledge. Data, information. And it can go any which way.

I have personally lived through the destructive power of knowledge. Unfortunately, when you get to the point where you know too much — and you can definitely feel it — it’s too late to go back.

Knowledge can be addictive, stirring up cravings for more, more, more. Knowledge can be harmful, intel turned on its edge as tool of masochism (have you stalked an ex?) or weaponized against someone else. Most offensively, knowledge can trick us into extrapolating stories and foregone conclusions — into a false sense of certainty.

The greatest trick that knowledge ever pulled was

convincing us we knew anything at all.

Samudhaya is the second of the Four Noble Truths in Buddhism. It relates to the cause of our suffering, which is our desire for permanence in a fundamentally impermanent world (and thus everything that desire drives us to do).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Birdseed to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.